SOME OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL POEMS INSPIRED

BY THE ETERNAL MESSAGE OF GREECE

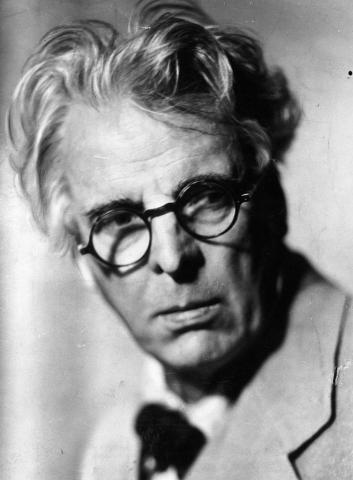

THE GREEK POEMS OF

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

THE SORROW OF LOVE

The brawling of a sparrow in the eaves,

the brilliant moon and all the milky sky,

and all that famous harmony of leaves,

had blotted out man’s image and his cry.

A girl arose that had red mournful lips

and seemed the greatness of the world in tears,

doomed like Odysseus and the labouring ships

and proud as Priam murdered with his peers;

arose, and on the instant clamorous eaves,

a climbing moon upon an empty sky,

and all that lamentation of the leaves,

could but compose man’s image and his cry.

TWO SONGS FROM A PLAY

I saw a staring virgin stand

where holy Dionysus died, and tear the heart out of his side,

and lay the heart upon her hand

and bear that beating heart away;

and then did all the Muses sing

of Magnus Annus at the spring,

as though God’s death were but a play.

Another Troy must rise and set,

another lineage feed the crow,

another Argo’s painted prow

drive to a flashier bauble yet.

The Roman Empire stood appalled:

it dropped the reins of peace and war

when that fierce virgin and her Star

out of the fabulous darkness called.

In pity for man’s darkening thought

he walked that room and issued thence

in Galilean turbolence;

the Babylonian starlight brought

a fabulous, formless darkness in;

odour of blood when Christ was slain

made all Platonic tolerance vain

and vain all Doric discipline.

Everything that man esteems

Endures a moment or a day

Love’s pleasure drives his love away,

the painter’s brush consumes his dreams;

the herald’s cry, the soldier’s tread

exhaust his glory and his might:

whatever flames upon the night

man’s own resinous heart has fed.

LEDA AND THE SWAN

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

by the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

he holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

but feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

the broken wall the burning roof and tower

and Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

so mastered by the brute blood of the air,

did she put on his knowledge with his power

before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

(1923)

SAILING TO BYZANTIUM

I

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees,

- those dying generations - at their song,

the salmon-falls, the mackerels-crowded seas,

fish, flesh, or fowl, commend al summer long

whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unaging intellect.

II

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

for every tatter in its mortal dress,

nor is there singing school but studying

monuments of its own magnificence;

and therefore I have sailed the seas and come

to the holy city of Byzantium.

III

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

as in the gold mosaic of a wall,

come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

and be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

and fastened to a dying animal

it knows not what it is; and gather me

into the artifice of eternity.

IV

Once out of nature I shall never take

my bodily form from any natural thing,

but such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

of hammered gold and gold enamelling

to keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

or set upon a golden bough to sing

to lords and ladies of Byzantium

of what is past, or passing, or to come.

(1927)

BYZANTIUM

The unpurged images of day recede;

The Emperor’s drunken soldiery are abed;

night resonance recedes, night-walkers’ song

after great cathedral gong;

a starlit or a moonlit dome disdains

all that man is,

all mere complexities,

the fury and the mire of human veins.

Before me floats an image, man or shade,

Shade more than man, more image than a shade;

for Hades’ bobbin bound in mummy-cloth

may unwind the winding path;

a mouth that has no moisture and no breath

breathless mouths may summon;

I hail the superhuman;

I call it death-in-life and life-in-death.

Miracle, bird or golden handiwork,

more miracle than bird or handiwork,

planted on the star-lit golden bough,

can like the cocks of Hades crow,

or, by the moon embittered, scorn aloud

in glory of changeless metal

common bird or petal

and all complexities of mire or blood.

At midnight on the Emperor’s pavement flit

Flames that no faggot feeds, nor steel has lit,

nor storm disturbs, flames begotten of flame,

where blood-begotten spirits come

and all complexities of fury leave

dying into a dance,

an agony of trance,

an agony of flame that cannot singe a sleeve.

Astraddle on the dolphin’s mire and blood,

Spirit after spirit! The smithies break the flood,

The golden smithies of the Emperor!

Marbles of the dancing floor

break bitter furies of complexity,

those images that yet

fresh images beget,

that dolphin-torn, that gong-tormented sea.

(1930)

AFTER LONG SILENCE

Speech after long silence; it is right,

all other lovers being estranged or dead,

unfriendly lamplight hid under its shade,

the curtains drawn upon unfriendly night,

that we descant and yet again descant

upon the supreme theme of Art and Song:

bodily decrepitude is wisdom; young

we loved each other and were ignorant.

THE PRESENT OF HARUN AL-RASHID

Kusta Ben Luka is my name, I write

to Abd Al-Rabban; fellow-roysterer once, now the good Caliph’s learned Treasurer,

and for no ear but his.

Carry this letter

through the great gallery of the Treasure House

where banners of the Caliphs hang, night-coloured

but brilliant as the night’s embroidery,

and wait war’s music; pass the little gallery;

pass books of learning from Byzantium

written in gold upon a purple stain,

and pause at last, I was about to say,

at the great book of Sappho’s song; but no,

for should you leave my letter there, a boy’s

love-lorn, indifferent hands come upon it

and let it fall unnoticed to the floor.

Pause at the Treatise of Parmenides

and hide it there, for Caliphs to world’s end

must keep that perfect, as they keep her song,

so great its fame.

When fitting time has passed

the parchment will disclose to some learned man

a mystery that else had found no chronicler

but the wild Bedouin. Though I approve

those wanderers that welcomed in their tents

what great Harun Al-Rashid, occupied

with Persian embassy or Grecian war,

must needs neglect, I cannot hide the truth

that, wandering in a desert, featureless

as air under a wing, can give birds’ wit.

In after time they will speak much of me

And speak but fantasy. Recall then year

when our beloved Caliph put to death

his Vizir Jaffer for an unknown reason;

“If but the shirt upon my body knew it

I’d tear it off and throw it in the fire.”

That speech was all that the town knew, but he

seemed for a while to have grown young again;

seemed so on purpose, muttered Jaffer’s friends,

that none might know that he was

conscience struck –

but that’s a traitor’s thought. Enough for me

that in the early summer of the year

the mightiest of the princes of the world

came to the least considered of his courtiers;

sat down upon the fountain’s marble edge

one hand amid the goldfish in the pool;

and thereupon a colloquy took place

that I command to all the chroniclers

to show how violent great hearts can lose

their bitterness and find the honeycomb.

“I have brought a slender bride into the house;

you know the saying, ‘Change the bride with spring,’

and she and I, being sunk in happiness,

cannot endure to think you tread these paths,

when evening stirs the jasmine bow, and yet

are brideless.”

But such as you and I do not seem old

like men who live by habit. Every day

I ride with falcon to the river’s edge

or carry the ringed mail upon my back,

or court a woman; neither enemy,

game-bird, nor woman does the same thing twice;

and so a hunter carries in the eye

a mimicry of youth. Can poet’s thought

that springs from body and in body falls

like this pure jet, now lost amid blue sky,

now bathing lily leaf and fish’s scale,

be mimicry?”

“What matter if our souls

are nearer to the surface of the body

than souls that start no game and turn no rhyme!

The soul’s own youth and not the body’s youth

Shows through our lineaments. My candle’s bright,

my lantern is too loyal not show

that it was made in your great father’s reign.”

“And yet the jasmine season warms our blood!”

“Great prince, forgive the freedom of my speech:

you think that love has seasons, and you think

that if the spring bear off what the spring gave

the heart need suffer no defeat; but I

who have accepted the Byzantine faith,

that seems unnatural to Arabian minds,

think when I choose a bride I choose for ever;

and if her eye should not grow bright for mine

or lighten only for some younger eye,

my heart could never turn from daily ruin,

nor find a remedy.”

“But what if I

have lit upon a woman who so shares

your thirst for those old crabbed mysteries,

so strains to look beyond our life, an eye

that never knew that strain would scarce seem bright,

and yet herself can seem youth’s very fountain,

being all brimmed with life?”

“Were it but true

I would have found the best that life can give,

companionship in those mysterious things

that make a man’s soul or a woman’s soul

itself and not some other soul.”

“That love

must needs be in this life and in what follows

unchanging and at peace, and it is right

every philosopher should praise its opposite

it makes my passion stronger but to think

like passion stirs the peacock and his mate,

the wild stag and the doe; that mouth to mouth

is a man’s mockery of the changeless soul.”

And thereupon his bounty gave what now

can shake more blossom from autumnal chill

than all my bursting springtime knew. A girl

perched in some window of her mother’s house

had watched my daily passage to and fro;

had heard impossible history of my past;

imagined some impossible history

lived at my side; thought time’s disfiguring touch

gave but more reason for a woman’s care.

Yet was it love of me, or was it love

Of the star mystery that has dazed my sight,

perplexed her fantasy and planned her care?

Or did the torchlight of that mystery

pick out my features in such light and shade

two contemplating passions chose one theme

through sheer bewilderment? She had not paced

the garden paths, nor counted up the rooms,

before she had spread a book upon her knees

and asked about the pictures or the text;

and often those first days I saw her stare

on old dry writing in a learned tongue,

on old dry faggots that could never please

the extravagance of spring; or move a hand

as if that writing or the figured page

were some clear cheek.

Upon a moonless night

I sat where I could watch her sleeping form,

and wrote by candle-light; but her form moved,

and fearing that my light disturbed her sleep

I rose that I might screen it with a cloth.

I heard her voice, “Turn that I may expound

what’s bowed your shoulder and made pale your cheek”;

and saw her sitting on the bed;

or was it she that spoke or some great Djinn?

I say that Djinn spoke. A live-long hour

she seemed the learned man and I the child;

truths without father came, truths that no book

of all the uncounted books that I have read,

nor thought out of her mind or mine begot,

self-born, high-born, and solitary truths,

those terrible implacable straight lines

drawn through the wandering vegetative dream, even those truths that when my bones are dust

must drive the Arabian host.

The voice grew still,

and she lay down upon her bed and slept,

but woke at the first gleam of day, rose up

and swept the house ad sang about her work

in childish ignorance of all that passed.

A dozen nights of natural sleep, and then

when the full moon swam to its greatest height

she rose, and with her eyes shut fast in sleep

walked through the house. Unnoticed and unfelt

I wrapped her in hooded cloak, and she,

half running, dropped at the first ridge of the desert

and there marked out those emblems on the sand

that day by day I study and marvel at,

with her white finger. I led her home asleep

and once again she rose and swept the house

in childish ignorance of all that passed.

Even to-day, after some seven years

when maybe thrice in every moon her mouth

murmured the wisdom of the desert Djinns,

she keeps that ignorance, nor has she now

that first unnatural interest in my books.

It seems enough that I am there; and yet,

old fellow-student, whose most patient ear

heard all the anxiety of my passionate youth,

it seems I must buy knowledge with my peace.

What if she lose her ignorance and so

dream that I love her only for the voice,

that every gift and every word of praise

is but a payment for that midnight voice

that is to age what milk is to a child?

Were she to lose her love, because she had lost

her confidence in mine, or even lose

its first simplicity, love, voice and all,

all my fine feathers would be plucked away

and I left shivering. The voice has drawn

a quality of wisdom from her love’s

particular quality. The signs and shapes;

all those abstractions that you fancied were

from the great Treatise of Parmenides;

all, all those gyres and cubes and midnight things

are but a new expression of her body

drunk with the bitter sweetness of her youth.

And now my utmost mystery is out.

A woman’s beauty is a storm-tossed banner;

under it wisdom stands, and I alone –

of all Arabia’s lovers I alone –

nor dazzled by the embroidery, nor lost

in the confusion of its night-dark folds,

can hear the armed man speak.